By Elysse DaVega

On December 9, workers at a Buffalo Starbucks voted to form the first union that the coffeehouse chain has seen in its over 8,000 locations. Bernie Sanders acknowledged it on his Instagram page, calling it a “historic achievement.” It’s obviously a big deal.

SBWorkers United’s victory is a fitting close to 2021, which has seen several large-scale labor strikes and union call-outs. From hospitals to cereal factories, this year has shone a light on the struggle for labor rights and, most importantly, corporate response to these demands.

But what can we learn from these individual victories, some of which are still in the works?

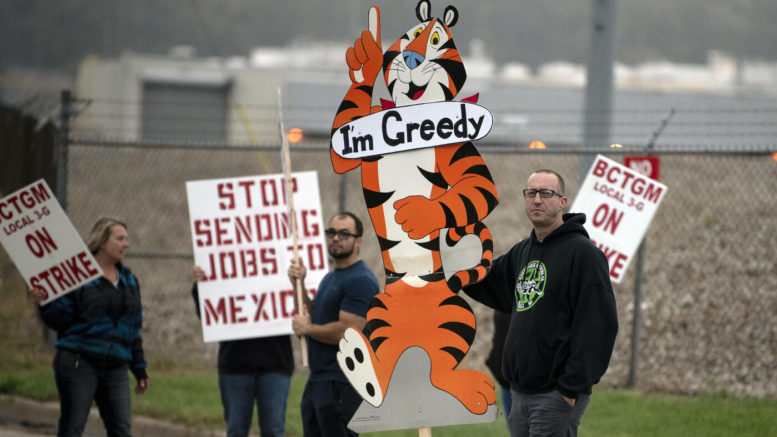

Kellogg’s

The strike against the breakfast cereal manufacturer began on Oct. 5, and we still have yet to see its end.

Kellogg’s workers’ plight surged from disagreements on a new labor contract. Their union, Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union (BCTGM) had been in talks with the company for over a year to decrease a pay gap between ‘transitional’ junior workers and ‘legacy’ senior workers, shorten work days and obtain more benefits.

These talks had been inconclusive, driving tensions higher and higher. Finally, these tensions brought workers to a strike in early October, causing Kellogg’s to bring in strikebreakers to relieve the slowed production.

At one point, union reps reported that Kellogg’s even threatened to move production to Mexico, where labor runs cheaper than it ever could here.

Since the strike started, BCTGM and Kellogg’s have been working to come to a fairer labor contract. However, on Dec. 7, Kellogg’s counter offer fell short: 3% raises with future cost of living adjustments.

As of now, Kellogg’s has begun to hire new permanent employees to replace striking ones.

The future of Kellogg’s workers on strike is uncertain, but what is certain is that Kellogg’s, like many other companies, doesn’t hesitate in letting their workers know that they are ultimately replaceable. Workers knowing their value is one of the greatest threats to seamless production, so devaluing them is the only possible way out. It’s a bastion of corporate ideology that will be used as leverage time and time again.

Amazon

Last year, Amazon saw protests, walk-outs and strikes demanding better pay and COVID-19 protections. It was one of the most turbulent years that Amazon has had in a while.

This year, almost as an annual tradition, Amazon workers in 20 countries held strikes and protests on Black Friday to demand pay boosts, longer breaks, sick leave and disclosure of COVID-19 protocol. Over 70 unions teamed up as part of the ‘Make Amazon Pay’ campaign, including Greenpeace and Amazon Workers International.

Amazon made a statement, saying that they’ve “already made headway” on these demands, but the specificity stops there.

Amazon reported $8.1 billion in profit in April, marking a 220% increase from the same period last year. The company has hired over 450,000 new people since the beginning of the pandemic.

They’re obviously not slowing down any time soon, so interrupting the company’s busiest season of the year is likely one of the only things workers can do to catch the attention of corporate and of the public.

Amazon is clearly a company that can adapt in times of difficulty, but it shouldn’t solely grow to its own benefit. With more staff comes higher expectations, and they have yet to meet these fully.

2020 was a tough year for the super-company and they still have a lot of damage to repair. We’ve all seen their new smiling worker ad campaign, but how can they really gain back our trust?

Frito-Lay

The 20-day strike stretched from July 5 to July 23, protesting Frito-Lay’s mandatory overtime policy and “suicide” shifts — 12-hour shifts, 7 days a week.

Workers said that due to COVID-19-related staffing shortages, some of them had been forced to work schedules that left them only 8 hours to rest and spend time with their families before they had to come in for their next shift.

600 workers comprising 80% of the company’s Topeka plant began the strike with the support of BCTGM, the same union that would support Kellogg’s workers’ later on.

PepsiCo, Frito-Lay’s parent company, called the workers’ claims “grossly exaggerated” and stated that they had already met the terms of another labor contract proposed by BCTGM.

The company denied any wrongdoing and said that the strike happened because of union leadership, who were “out of touch with the sentiments of Frito-Lay employees.”

At the end of the 20 days and a chip shortage in Kansas, workers had won negotiations for one guaranteed day off per week, as well as the elimination of forced suicide shifts.

Frito-Lay may have conceded, but their failure to admit wrongdoing leaves something to be desired in the aftermath. If nothing was wrong with company policy, why was it the only thing that changed?

Also, the company blaming union officials instead demonstrates an old trick to turn strikers against each other and weaken the collective cause. Amazon and Walmart have even been caught spying on unions to intimidate them, even sneaking into union group chats in some cases. It rarely works.

These three labor strikes look similar to many strikes from years before, but we have to take a wider view. While the workforce has been stretched thin during the pandemic, countless companies have enriched themselves further. However, they’re still so hesitant to give back, to adapt to working people’s needs.

2021’s wave of strikes shows that to be listened to, many working class people have no choice but to take drastic measures. The ideas behind these measures are the same ideas contributing to The Great Resignation.

Companies can’t continue to treat their employees as disposable. Workers have realized their worth. This year’s progress means that there’s no going back.

Be the first to comment on "The Uptick of Labor Strikes in 2021 and What They Mean"