By Joules Margot

16-year-old Susan “Chubby” Palmer Pollock struggled with arithmetic. She made a 78 in the subject and as most teenagers would, promised to “do better next time.” Unlike most teenagers, however, Chubby did not attend a modern high school. The year, for her, was 1909.

In Saint Augustine, Florida, where the most notable historical figure is business tycoon Henry Flagler, the experiences of middle-to-working-class individuals are often forgotten. The stories of adolescents, particularly, are underreported in the historical record. Archivists at Flagler College are working to change this with their project, “Beyond the Line.”

Archives specialist Jolene DuBray and assistant professor Dr. Jeanette Vigliotti of Flagler College began to uncover Chubby’s story when another research project lost traction. While attempting to find evidence of potential influences of the Gullah Geechee culture on local agriculture, the two sifted through unprocessed donations to the archives.

“And in those [unprocessed donations], there was this box of letters that we found from 1909,” DuBray said. “So, we started reading these letters and we realized that these letters were written by a 16-year-old girl named Susan Pollock who goes by Chubby…and she’s writing letters to her secret husband because she’s only 16 years old and she’s hiding it from the community.”

20-year-old George Ira Pollock, an employee on Flagler’s FEC Railway, was Chubby’s forbidden beau. By March 12th, 1909, the two had been wed for approximately two weeks.

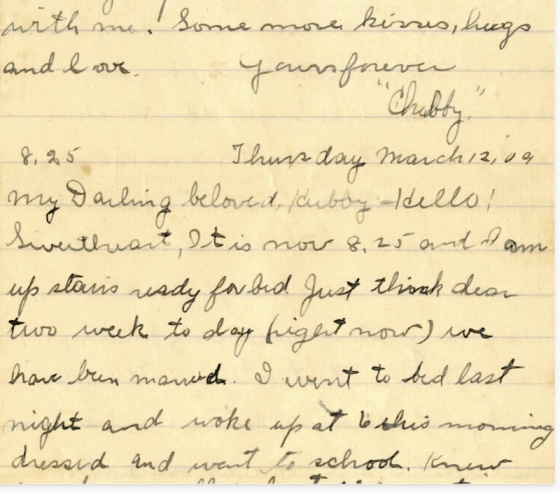

“Oh! My darling husband, get work where you can and do please come back for me as soon as possible, for dear, I cant stay away from my love very long,” Chubby wrote on March 2, 1909. “Whit lots of love and kisses. ‘Your true devoted wife’ [sic].”

For the archivists, “the letters are basically a slice-of-life in St. Augustine from a woman’s perspective in 1909,” Vigliotti said. She emphasizes the “diaristic account” Chubby’s letters provide of the time period.

“It’s granular detail about daily life from a working class family’s perspective, which is very different than normally how we talk about St. Augustine in the early 1900s,” Vigliotti said. “The end of the Gilded Age, beginning of the progressive era, this is just like a shift.”

The letters are a primary source of young adulthood in the Progressive Era for a St. Augustinian. Chubby often writes about her family, their day-to-day activities, finances, house chores, and the longing she feels for her husband traveling on the railroad.

“You certainly did do some riding to get so far away from me in such a short time, but darling, you can get back here just as quick [sic],” Chubby wrote on March 12, 1909.

The address line of the envelope reads:

“Mr. George Ira Pollock,

Sommerset

Ky.”

Despite not having a direct account from George to Chubby about his work, the strain of life on the railway is palpable.

“We can read in these letters how stressful it was, how dangerous it was to work on the railway, how it affected your family to be away from home so long,” DuBray said.

This impact of the FEC Railway on the everyday worker is a large part of DuBray and Vigliotti’s research into the St. Augustine community and Northeast Florida from the mid-1880s to the late 1960s. “Beyond the Line” aims to capture the impact of the movement and migration surrounding the railway on marginally underrepresented communities.

“What we’re focusing on in our research is race, class and gender,” DuBray said. “Communities from their point of view.”

Another focal point of “Beyond the Line” is the area of Manhattan Beach (a historic area of Jacksonville), which explores the Black worker experience in relation to the FEC Railway.

“A stretch of the breach was sold by FEC to some of its African American employees so that they could create their own beach,” DuBray said. “This was in 1907 when they did that, and there’s a huge saga that happens whenever people wanted that land back.”

Per the Historic Manhattan Beach, Florida Marker, “Manhattan Beach was Florida’s first African American beach resort.”

Mack Wilson and William Middleton, Black entrepreneurs, constructed pavilions which supplied beach-goers with “entertainment, bathing suit rentals, dining, and lodging.” However, “Beyond the Line” states that “through a series of exploitative real estate deals and the 1932 closure of the FEC rail extension, access to the Manhattan Beach diminished and eventually closed.”

As their research progresses, DuBray and Vigliotti will be searching for more connections between Black residents of Northeast Florida and FEC railway workers.

“During the Civil Rights movement in St. Augustine, concurrent with that, there were also a lot of labor protests going on about the FEC railway, and something we’re interested in looking into [is was] there any cross-protests going on?” Vigliotti said.

In collaboration with the St. Augustine Historical Society, DuBray and Vigliotti plan on opening a physical exhibit of the letters in 2027. Until then, they “have a lot of unanswered questions, [and] a lot of leads to chase up,” according to Vigliotti.

In the meantime, to learn more about Chubby and George’s story, Manhattan Beach, and “Beyond the Line,” visit Beyond the Line’s digital map.

Be the first to comment on "The Hidden Lives of Historic St. Augustine"