By Katherine Lewin | gargoyle@flagler.edu

Artwork by Carolina Torres

On July 27, 2015, Villatoro thought he was being released from the Washington State Penitentiary. He was wrong. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) came for him instead, which he didn’t understand. He had had a green card for decades after immigrating to the United States from Guatemala.

Villatoro was transported from the state penitentiary to the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington. It’s an immigration prison owned by The GeoGroup, Inc.–one of the largest and most profitable private prison corporations in the United States.

Within 24 hours of arriving at the Northwest Detention Center, Villatoro tried to hang himself again. He ended up spending an additional two years in the NWDC. He said those two years and two months were a psychological and physical nightmare for him. He didn’t know why he was still being held after serving his time in state prison and had no idea how long he would continue to be detained.

Within five months of being in the NWDC, Villatoro witnessed a fight between the three main Latino gangs in the center: the Sureños, Norteños and Paisas. Villatoro reported the fight, thinking that he might be helping to save lives, but he wanted to remain anonymous to protect himself and his family from gang retaliation. The raid of the cells that followed turned up pornographic magazines and weapons made out of toothbrushes, commonly known as “shanks.”

Villatoro wanted redemption in reporting the fight, but earned enemies instead. According to Villatoro, a corrections officer at the center known as T. Moon was working with the Sureños, smuggling contraband items in and out of the NWDC for them. Moon told one of the gang ringleaders, S. Castellanos, that Villatoro was the one who reported the fight. Castellanos soon made death threats against Villatoro and his family. Villatoro reported this to the Tacoma Police Department. According to an incident report filed on Feb. 2, 2017, Villatoro said he feared for his life and the lives of his wife and children.

An internal investigation at the NWDC led to Moon’s firing. Shortly after that, Villatoro was taken to solitary confinement, where he would remain for one year and nine months. Officers told Villatoro that he was being moved there for protection against Castellanos, but Villatoro believes he was left in “the hole,” as solitary confinement is known, for reporting Moon.

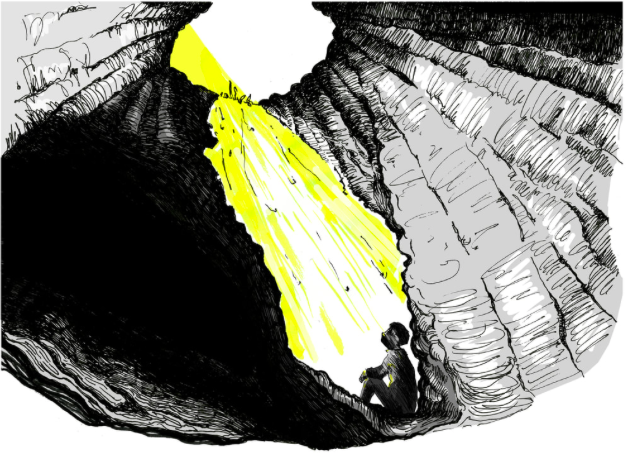

For one year and nine months, Villatoro did not see the light of day or receive even a visit from his lawyer. He sat in near darkness and thought about his family, his regrets and his faith. He tried to block out persistent suicidal thoughts and forget the sexual assault that still haunted him.

Villatoro was finally, inexplicably, released from the NWDC in the fall 2017. He is now free but unemployed, citing difficulties finding work because of his felony record and the fact that he is on medication for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. After five years of absence, his wife left him. He has no money and nowhere to go, so he lives mainly on the streets in Kent, Washington.

“Sometimes I start cutting my arms just to release the frustration that I have. What I went through, I consider torture. It’s amazing what the system is doing to people,” Villatoro said.

The prison industry and its supporters and beneficiaries may say Villatoro’s story is an isolated instance, a fluke. But what Villatoro and the hundreds of thousands of immigrants that are detained in private prisons each year experience may indicate corruption that permeates the institution of corporation-owned, for-profit prisons.

Alex Friedmann, a writer and an editor of Prison Legal News, has been covering corrections for more than 20 years and is a vocal critic of private prisons. He believes that incarcerating people for a profit creates a higher possibility of corruption.

“Literally, you can put a dollar figure on each inmate that is held at a private prison,” Friedmann told NBC News. “They are treated as commodities. And that’s very dangerous and troubling when a company sees the people it incarcerates as nothing more than a money stream.”

Complaints of sexual assault, physical assault and mental abuse from both ICE officials and corrections officers have been coming to light in the past several years as the private prison sector has come under further scrutiny. A report put together by the Office of the Inspector General and released in August of 2016 concluded that inmates at prisons owned by GeoGroup and CoreCivic are nine times more likely to be placed on lockdown than inmates at federal prisons and were frequently placed in solitary confinement.

Both the United Nations and former inmates have described solitary confinement as a form of torture. At private centers, violence between inmates was found to be 28 percent more prevalent. The report also found that inmates are more likely to report negligent medical care, abuse from correctional officers and bad food. Since immigrants are being criminally prosecuted for entering or re-entering the country, they can be held for months and even years in these conditions before going through civil deportation proceedings.

Robert Painter, an immigration lawyer who has worked in Central Texas for the last five years, said that complaints from his clients about conditions inside the detention centers are common.

“They tend to be complaints about mistreatment from either ICE officials or the private contractors who operate the facilities. There are complaints that the food is really bad, that it’s spoiled, or they’re not getting appropriate health care,” Painter said. “We’ve heard cases about people who require specific types of diabetes medication and they’re not getting it, or not getting adequate mental health care.”

One of the most recent allegations against private prisons in both Washington and California is that immigrants are being exploited for cheap labor. Several lawsuits are pending across the country, including one that has been filed in Washington State against the NWDC. The state attorney general, Bob Ferguson, is suing The GeoGroup, Inc., the owner of the NWDC. Ferguson alleges that GeoGroup is violating the state’s minimum-wage laws by asking immigrant detainees to work for $1 a day or less. When Ferguson announced the lawsuit on Sept. 20, 2017, Ferguson said in a statement that the GeoGroup was “making millions of dollars by drastically underpaying its workers.”

Some of the people most familiar with the private prison system and the problems and ethical dilemmas it presents are the lawyers who have dedicated their careers to helping immigrants safely and quickly navigate the complicated and often corrupted process of entering the country and obtaining legal papers.

NGOs like the Cuba Libre Foundation and movements like the Northwest Detention Center Resistance are popping up all over the United States in response to President Trump’s tough stance on immigration and successful lobbying by private prisons.

Maru Villalpando, the co-founder of the Northwest Detention Center Resistance, has been an activist for immigration rights in Washington State since the NWDC first opened its doors in 2004. Villalpando is originally from Mexico City and has been living in Washington for 25 years.

The NWDC Resistance is a group of about 20 people who work to provide better conditions for detained immigrants in the center. She has successfully supported several hunger strikes inside and organized a human blockade in 2014 that stopped vehicles from taking people out of the center to deport them.

Working with people inside the Northwest Detention Center is how Villalpando met Villatoro and thousands of others like him who were taken advantage of by the system. Villalpando is one of many who believes that private prisons contracted by ICE are exploiting undocumented and documented immigrants alike, as in the case of Villatoro.

“We work directly with people who have been detained, so we get the information from them about detention conditions and exploitation of people inside. We gather this information, we go and put pressure on the institutions, and on legal organizations to take pieces of it and help us attack those pieces,” Villalpando said. “So for example, during the hunger strikes of this year, we were able to put pressure on the attorney general’s office to actually investigate the conditions of the $1 -a-day, volunteer, quote-on-quote ‘work program.’ And they found that yes, there were grounds for a lawsuit and they filed a lawsuit against GEO for not paying them minimum wage.”

Villalpando believes that the only solution is to abolish ICE and revert the immigration system to a pre-Reagan era before the former President Reagan made looking for work without a social security number illegal. Without drastic changes, Villalpando believes that the private prison system will continue to exploit immigrants.

“What we want is really to end with all detentions, end with all deportations, and dismantle the whole Immigration Customs Enforcement institution,” Villalpando said. “The status quo right now is to ensure that deportations continue, that deportations are profitable in that people like me are really becoming cheap labor.”

It’s not difficult for the private detention centers contracted by ICE to detain immigrants indefinitely and maintain low living standards to maximize prison profits. Exposing human rights violations are not easy. Because corporations own the centers, they are not subject to the same transparency laws required for state and federal prisons.

According to a study conducted by the International Journal of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education, vague contracts, the agency problem of conflict of interest, and the lack of open access laws, specifically, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), contributed to maladministration in private prisons.

Supporters of privatization argue that privately owned detention centers are safer and more cost-effective. However, private prisons may actually cost America’s taxpayers more money. According to a study by Economic Affairs, researchers identified economic problems such as incomplete contracting and moral and ethical issues. Measuring the actual cost-effectiveness of private prisons is challenging and often inconclusive.

At the end of Barack Obama’s presidency, the Justice Department decided to phase out private prisons, concluding that they are less safe and less effective at reforming inmates.

President Trump reversed that initiative upon taking office. GeoGroup, one of the two largest private prison companies in the United States, donated $250,000 to the president’s inauguration campaign, the company’s vice president of corporate relations, Pablo Paez, told USA Today. CoreCivic, the other largest private prison corporation, also donated $250,000 to the inauguration, according to filed congressional reports.

Painter, who does most of his work pro-bono for immigrants through grants, believes that privatization of the prison system can lead only to corruption.

“Once you create a system where there is a strong profit motive for detention, people start marking decisions based on what’s going to maximize their profits, not based on what is the appropriate thing to do from a human rights perspective,” Painter said. “There are billions of dollars made each year through these contracts. It leads a lot of us to question is this really about doing what’s best from an immigration enforcement perspective? Or is this about making some people rich?”

When asked for comment on Villatoro’s experience in the NWDC, Paez referred all questions to ICE. At the time of publication of this article, ICE did not reply to requests for comments on the allegations from Villatoro.

Be the first to comment on "One year and 9 months: Solitary confinement hell for detained immigrants"