By Abby Bittner

Being the oldest city in America, St. Augustine is overflowing with history, from pirate invasions to political figures visiting. However, a more hidden part of St. Augustine’s history lies in Lincolnville, a smaller section of town that was a hotspot during the Civil Rights period. While many tend to forget about this area of St. Augustine, it holds historical landmarks from the Civil Rights period that are just as important to learn about today. Local Historian David Nolan has surveyed many buildings in the area dating back to the 1970s and was active in the Civil Rights movement a decade prior. While the 75-year-old is now retired, his curiosity for finding hidden history in Lincolnville is still shining bright.

In 1978, Nolan surveyed the old buildings in town for the St. Augustine Preservation Board.

“I was told two things right at the beginning. One was, ‘You must never mention the name of Martin Luther King in St. Augustine,’” he said. “The second thing I was told was, ‘Don’t waste any time in Lincolnville, there’s no history down there.’ I was the wrong person to say that to.”

Rather than a traditional introduction to St. Augustine, Nolan got to discover it from a much more intimate perspective.

“I spent the next two years walking up and down every street. Stopping in front of every house, writing an architectural description of it, and then going back through old records of the courthouse, the Historical Society and old maps to try and date every building, and to try and find out some significant things about it,” Nolan said. “That was a wonderful way they get to learn the city.”

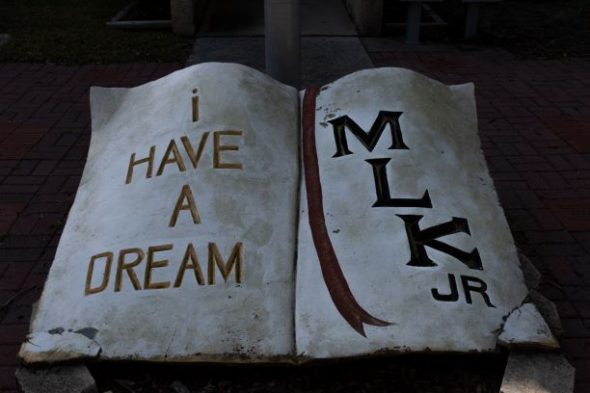

Many parts of St. Augustine’s history have fascinated Nolan, but moments involving Martin Luther King Jr. specifically caught his interest.

“The FBI thought this would be the place Martin Luther King was killed. I knew that background, but what I really wanted to know was where did Martin Luther King stay?” Nolan said.

One of his greatest history teachers, Henry Twine, helped him to scout out these places. Twine served for 10 years on the city commission and was the first Black vice mayor of St. Augustine.

“He was a man who loved history and made history, and he and his wife were the heart and soul of the civil rights movement. Shortly before he passed away in 1994, I said, ‘I want you to go around with me and point out every house you can remember where Martin Luther King stayed,’” said Nolan, adding that Twine pointed out three houses.

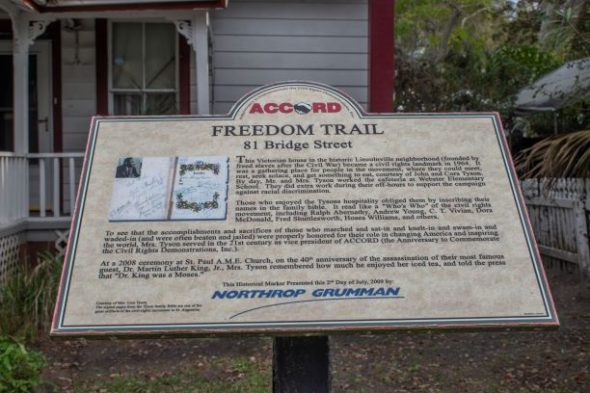

Eventually, they were marked as places Martin Luther King stayed at, with two of them included on the Freedom Trail. “Had I not done it then, who would have told me?”

The Freedom Trail marker can be seen, detailing the people who housed Martin Luther King during his stay.

Much of the history discussed in St. Augustine is portrayed via costumes, souvenir shops, and buildings fabricated to look older, and aims to attract tourists more than anything.

“You know, whenever they say St. George Street, they mean white history,” Nolan said. “It was fake buildings, funny costumes and all white history, that was really what St. Augustine presented to the world at that point. All history was St. George street and the tourist trap area, and most of the buildings you saw there were fake because they had been built within my lifetime and were designed to look older.”

For Nolan, it is a race against the clock to find the crucial historical sites of St. Augustine, and more specifically, Lincolnville.

“If you knock on the doors of 90% of the houses, somebody white will answer and they’ll know nothing of the history of Lincolnville,” he said. “That’s in danger, the historic memory of that is in danger of completely vanishing.”

While many of the historical records in St. Augustine are not going anywhere, Nolan yearns to find what is beyond what is already found.

“Old Spanish records that are in the Library of Congress are going to stay there. But, what’s not going to stay there is what’s in the attic of a 90-year-old person who is going to die in a year or two, and everything is going to go in the trash,” he said. “Family scrapbooks, old clippings, things like that will be gone forever.”

While his line of work seems to be mostly exciting, Nolan has also witnessed the removal of history downtown.

“The saddest moments I’ve seen have been the destruction of civil rights landmarks, like the Monson Motor Lodge on the bayfront, which was the only place in Florida Martin Luther King was arrested and where so many of the dramatic events of the civil rights movement took place,” he said of the landmark, which was home to the infamous acid pool image and was demolished in 2003.

Nolan has done plenty of digging for history — physically and metaphorically — from perusing through garage sales to even looking through what most people see as garbage.

“This is all we’re going to have to pass on to the future. Other than that, there’s nothing of interest and of substance, nothing that really brings it to life for the future. Part of it is the need to think ahead, plan ahead and get the material that if you don’t get now, it’s never going to be gotten. It’s going to be part of landfill.”

His priority is to uncover these historical moments, and to educate future generations about the truly hidden history in St. Augustine. “As a historian, I spent half my time looking backwards,” Nolan said. “But I spent part of my time looking ahead saying, ‘What’s the historian 50 or 100 years from now going to wish we had saved?’”

For more information about the history of Lincolnville and the Freedom Trail throughout St. Augustine, please visit https://accordfreedomtrail.org/

Be the first to comment on "Local Historian Seeks to Uncover Lincolnville’s Hidden Past"