By Matt Keene | gargoyle@flagler.edu

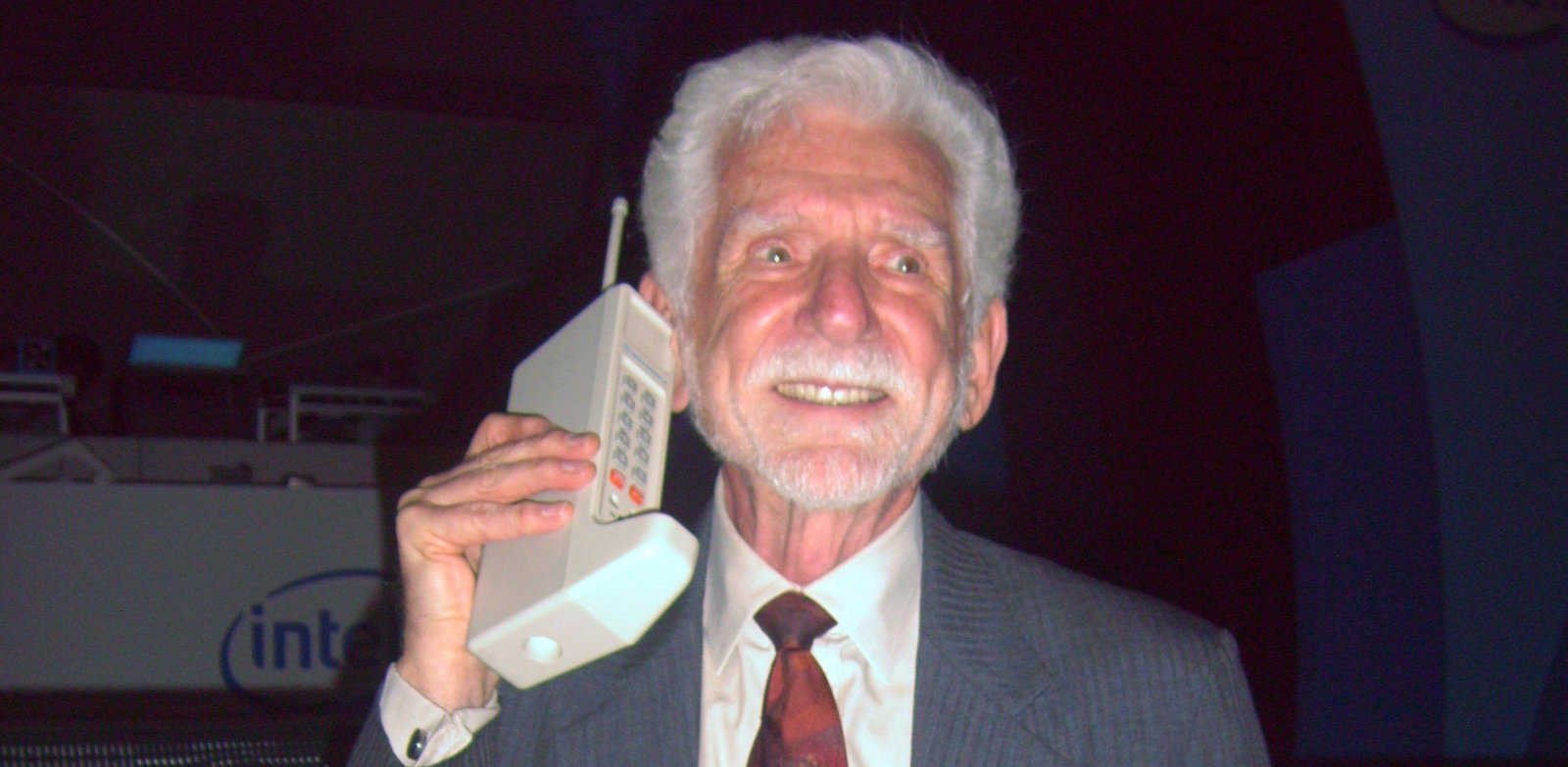

I am a child of Martin Cooper. This guy, right here:

If the name doesn’t ring a bell (pun very intended), Cooper was the inventor of the first commercially available cell phone, the Motorola DynaTAC 8000x. The DynaTAC weighed in at nearly two pounds, making it a stretch to actually call the phone mobile. Even Cooper said “the battery lifetime was 20 minutes, but that wasn’t really a big problem because you couldn’t hold the phone up for that long.”

The DynaTAC started selling in late fall of 1983, less than two years before I was born. At the time, it cost almost $4,000, which would be around $9,000 today, so as a kid I never found one wrapped up under the Christmas tree. This cellphone ran in a different social class than I did. It was an accessory for the rich, with the ability to store up to 30 numbers and occasionally have enough service to complete a call. But its presence shaped the United States I grew up in.

Today, DynaTAC’s genius children can be geolocated to within shouting distance of me nearly every minute of every day and shape just about everything I do. As evidenced by the Snowden revelations that began last year, much of the way these smartphones affect me is top-secret, classified and presumes that I am guilty of something worthy of government surveillance.

More than 20 years after the release of the DynaTAC, the first camera phone became available. It was 2003 and I was a senior in high school. I still ran around the world without a cellphone in hand or pocket, but the tide was changing. I occupied our house line for unspeakable hours at night, finding pounds of conversation in ounces of would-be texts.

I never saw a cellphone in the hands of my classmates. I can still vaguely recall the silence of a classroom without cellphones and the loudness of a courtyard where students shouted and laughed, immersed in a world that extended to the furthest visible distance and not one digital inch further.

Then came June 29, 2007. I was 22 and walking north on the toothy spine of the Appalachian mountains, in the middle of a more than 2,000 mile thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail. Up on the mountains, I still didn’t have a cellphone. I had calling cards. Wandering off the mountains, I would find a pay-phone and enter in a long-winded confirmation code before being able to “please deposit 50 cents for the next three minutes.”

While I was in the woods, Steve Jobs released the Apple iPhone. With a touchscreen and clean user interface, the iPhone captured the public’s attention, although even its first iteration couldn’t record video.

Invasion of Privacy

It was six years to the month from the first iPhone release to the first Snowden leak and on its heels came the cold reality of a world where digital privacy is scraped together in open-source communities like a Frankenstein David fighting a colonial Goliath.

According to studies conducted by Nielsen, smartphone penetration in the U.S. was around 10 percent one year after the first generation iPhone. By 2013, it jumped to more than 60 percent, equivalent to three out of every five people.

That same year, 2013, German news magazine Der Spiegel revealed that the NSA has the ability to tap into data from all the major smartphones, including emails, contacts and physical location. Declassified documents from the NSA showed how one of its surveillance programs collected as many as 56,000 emails from individuals not connected with terrorism and journalist Glenn Greenwald claimed that documents showed the NSA could track 1 billion cell phone calls every day.

Smartphones were everywhere. In everyone’s hands, pockets, ears, in the culture itself. They became a window into both the public and the private lives of ordinary citizens, tethered to the hip and the fingertip by a genuine desire for connection and community.

Edward Snowden

I don’t need to describe the feeling of being connected because more of you are plugged into that world than aren’t. What about what happens when you disconnect, though? When you step away from that wonderland of bits and bytes, that digital encyclopedia full of opportunity? How many have taken a break from that world once they’ve connected? For that matter, why would anyone want to?

I’d like to say that Snowden made me question my immersion in the digital world. I’m sure that’s what Snowden would like to hear. But, the truth is, it wasn’t Snowden. It was water damage.

My smart phone sped down an avalanche of malfunctions, choreographed by a disconnect in the phone’s ability to measure battery life. Apps wouldn’t run, phone calls would break off, leaving only a receiver muffling the sounds of a busy world. The phone would go black. Dull. Lifeless. A small, beautifully designed cuboid that had suddenly lost all purpose.

By late September of 2013, my frustration had turned into forfeiture. At the same time, the New York Times disclosed that the NSA uses Facebook and other social media platforms to create maps of the social connections of Americans. The Guardian revealed that the NSA stores the browsing history, account details, email activity, passwords and other metadata on millions of web users, whether the users are intentional targets of the agency or not.

I gave up on the phone, sticking it in a bag, out of sight and powered down. Even lifeless, I knew the smartphone was there. I still found comfort from its presence, like a dog refusing to leave the side of its dead master.

On October 30, 2013, the Washington Post revealed that the NSA has hacked into Google, Yahoo and Microsoft databases, allowing the agency direct, unencrypted access to almost all user data, including email, web searches, documents and photographs. That same month, the Washington Post published documents showing that the NSA collects over 250 million email inbox views and contact lists a year from services like Yahoo, Gmail and Facebook.

My smartphone was dead, but my digital prints were smeared all over. My Facebook friends, my concerned opinions, my photos, my emails, my documents, my sensitive account details were more than likely stitched together into a mosaic of who the government believes me to be. Of who they believe my friends to be.

In December, the Guardian, the New York Times and ProPublica revealed that the NSA, the FBI, the Pentagon and British intelligence agency GCHQ monitor online games such as World of Warcraft, Second Life and Xbox Live. The agencies use bulk data collection and human spies to monitor millions of people worldwide.

Disconnecting from it all

At this point, I have abandoned my smartphone.

Its benefits were many. When its use becomes the most apparent, I still find myself frustrated. One month ago, I was lost on the outskirts of Miami, trying to find my way west into the cypress sloughs of Fakahatchee, only I was being pulled further into the bowels of the sprawling city.

A smartphone would have told me where to go. It would have lit my path and sped me away. Instead, I was forced to feel discomfort. I was forced to ask a gas attendant. When the attendant didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Spanish, I flagged down a police officer.

As I strolled up to the officer’s car, I wondered what he thought of me. I wondered how I was being profiled.

Was I just some lost white kid? Was I a perceived threat? Or, was I, a Facebook user, a data trove of posts, personal pictures and missed events? Was I a Gmail user, with email messages to friends, family and colleagues, a mosaic of photographs and holiday messages and arcane details of my life? Was I an activist, arrested a decade ago for political expression, and connected to people who were connected to people who were connected to people who could possibly be concerned about the future of the land they lived on?

My communication with the police officer was transmitted through the air. It self-destructed milliseconds after it was sent. It was sincere and beneficial to both of us. Its records were left in memory, not in implication. And, for a few precious days as I disappeared into the humid ecoregion of the Everglades, the NSA was forced to wait alongside the rest of my digital friends and family for my photographs and my stories.

Be the first to comment on "Life beyond the smartphone: Finding digital peace of mind"