By Courtney Cox | gargoyle@flagler.edu

An elephant tusk is worth a 1000 words. China claims to bring the days of ivory trade to an end, while the U.S. now considers lifting the 2014 ban. Photo Credit: Elephants Alive

The Trump administration is weighing the ban of elephant ivory being imported into the U.S.

If the ban is lifted, it could set back the work conservationists and park rangers have devoted their livelihoods to.

In the past 10 years, 1,000 park rangers have been killed worldwide—80 percent by commercial poachers and armed militia, according to the Global Conservation.

China, which for years has been home to the world’s largest ivory market, is completely phasing out the ivory trade–they announced in 2016 that by the end of 2017, the ivory trade in China would be no-more, according to CNN.

On August 16, 2017, Wayne Lotter, one of the biggest names in African elephant conservation and a co-founder of PAMS (Practical Area Management System) Foundation in Tanzania, was shot dead in a taxi by someone authorities have reason to believe followed him that night.

Lotter faced a number of death threats in his career as a conservationist. And there is reason to believe that a member of the poaching industry could have had something to do with his death.

Tamsin Lotter, one of Wayne’s two daughters, has followed in her father’s footsteps of elephant conservation through field photography at Elephants Alive, where she works as a research assistant.

Tamsin’s father was an inspiration to not only her, but to conservationists from all around.

“He raised awareness, interacted with many parties that would help his cause including the Tanzanian government,” Tamsin said. “He walked the walk and talked the talk at so many levels that I feel he set a shining example for many conservationists. I am so proud of what he did.”

Still though, her father’s conservation work is not done. Ivory is still on the market and the elephant killings are “relentless,” Tamsin said.

“I think there is an infatuation with the ivory because it is easy to carve. It is a strong material and it’s been harvested and used for many decades. Only now, our numbers and greed far outweigh the number of elephants left in Africa. They are under fire and we, as a human race need to stop the relentless killing so that my dad did not die in vain,” Tamsin said. “Do we need to decorate our homes with ornaments that come from a species with close social ties as our own? I would prefer for us to realize at our core that we have evolved beyond this as a human race. We need to protect our dwindling wildlife with all that we have.”

Elephants are a keystone species, meaning other species depend on them for survival. In Northern Cameroon the carcass ratio of elephants, number of dead elephants found, in 2016 was 83 percent of the population. Without human intervention, it’s probable that this small population could go locally extinct, according to the Great Elephant Census.

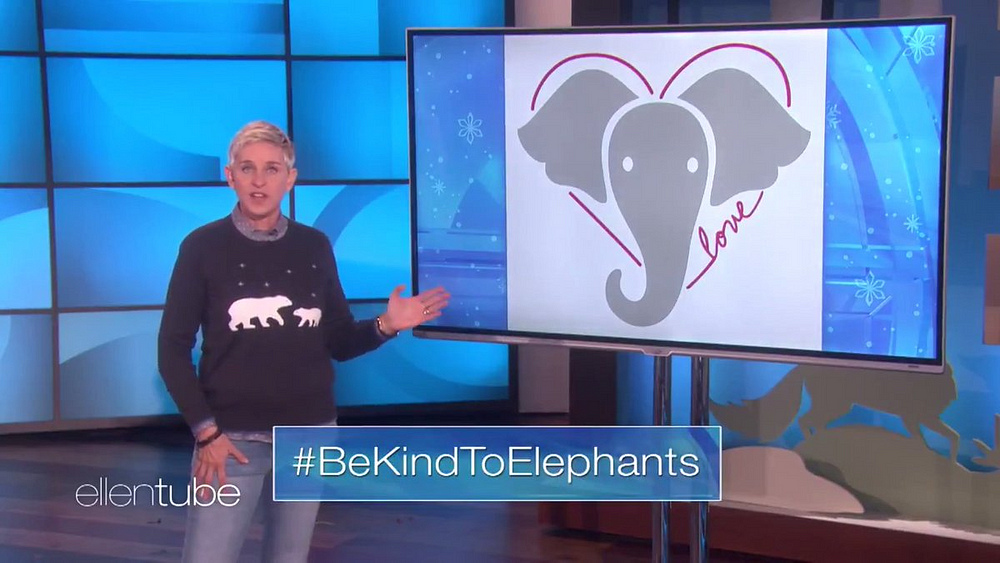

The introduction to the Trump administration’s plan created quite an uproar among conservationists and animal lovers on social media. Ellen DeGeneres even took initiative on her Instagram account posting a graphic design of an elephant inside a heart, caption reading: “I’m determined to do something about this,” accommodated with #BeKindToElephants.

For everyone who uses or retweets #BeKindToElephants, the Ellen Show will donate to the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust to help efforts of conserving elephants. Photo Credit: Scoopnest.com.

The attempt to begin allowing hunters to bring “trophy” elephants killed in Zimbabwe into the U.S. would have reversed the 2014 ban. However, Trump has now decided to put this plan on hold tweeting: “Put big game trophy decision on hold until such time as I review all conservation facts. Under study for years. Will update soon with Secretary Zinke. Thank you!”

The Global March for Elephants and Rhinos (GMFER) is a “global grassroots advocacy movement instrumental in changing national and international policy, as well as regulations and laws on behalf of mitigating and eradicating wildlife crime, poaching and trafficking,” Rosemary Alles, president of GMFER, said. Since Trump’s election, conservation progress and protection seems to be at stake, she said.

“The election of Trump has dealt a grave blow to wild creatures and wild places, nationally and globally; from dismantling reasonable and sound Obama era policies governing climate regulations, to threatening endangered species’ habitat and lives, the Trump administration poses a clear and present danger to wild creatures and wild lands everywhere,” Alles said.

Alles, who moved from the U.S. to South Africa to volunteer for biodiversity and the protection of charismatic megafauna, believes that “good work” will be undone if the ban is lifted.

“If the Trump administration decides to lift the ban on commercial ivory within the USA, years of good work by GMFER and other groups will be undone; thankfully, New York, California, Hawaii and Washington have state-level bans which are stronger than the prevailing federal rules and are (arguably) better enforced,” Alles said.

The 2014 ban, intended to end trade that threatened to run the world’s largest land animal extinct, was put in place on imports from Zimbabwe due to the lack of data on conservation efforts there. The Obama administration had said that for the first time, vendors had to be able to prove, undoubtedly, that any ivory for sale complied with the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

CITES (The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) had temporarily lifted the successful 1989 ban in 1999 and again in 2008, on commercial, international ivory. The on-and-off lifting of the ban created devastation among elephant populations, escalating poaching and wildlife trafficking, Alles said.

“During the same time period in which the 1989 ban was lifted, China also experienced an economic boom, sponsoring a burgeoning middle class with disposable income, desirous and capable of paying for ‘luxury items’ in the form of ivory, rhino horn, tiger bone, lion bone, pangolin scale etc.,” Alles said. “One could say, ‘it was the perfect storm’ in opposition to elephants, earth’s most charismatic terrestrial mammal was—yet again—in jeopardy.”

As it stands, the U.S. agency claims Zimbabwe’s actions are satisfactory where now hunting of that sort can be beneficial to the species, according to the New York Times.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service came to the conclusion that killing African elephant trophy animals in Zimbabwe, on or after Jan. 21, 2016, and on or before Dec. 31, 2018, would enhance the survival of the African elephant, according to a notice posted Nov. 17, 2017, by the Federal Register.

Dr. Melissa Southwell, an associate professor in the natural sciences department at Flagler College, joined the Peace Corps as an Agroforestry volunteer in Cameroon. She tries to look at the ivory perspective from both sides, but in the end, she chooses one.

“In the short term it seems tempting to sell off ivory stocks to increase availability of funds for enforcement. However, in the long term the only way to diminish poaching is to diminish the demand for ivory,” Southwell said.

In order to diminish these things, more awareness on the topic needs to be brought about, Southwell said.

“This only occurs through increased awareness and cultural change, which is a slow process, but one that is already beginning. A legal ivory market allows this material to remain as a social status symbol; in that scenario its value does not diminish and poachers do not relent until the elephants are gone,” Southwell said.

One company has taken charge in raising awareness and money for elephant conservation. Ivory Ella, an online clothing store that donates 10 percent of its profits to elephant conservation, launched in the spring of 2015 and has been a growing success since. The company to date has raised $1,130,717 in donations, according to their online store.

In the news of Trump’s teetering ivory talk, Ivory Ella gave this statement:

“Since 2015 Ivory Ella has supported the elephants. Now more than ever we stand with our partner, Save The Elephants, and we remain committed to the health and wellbeing of elephants.”

In Dover, Ohio, a family has been passing the craft of carving on from generation to generation. The family of artisans has been crafting in bone and ivory since 1902 when Ernest Warther started a business of knife creating and carving, which he then passed on to his son, David.

Photo Credit: David Warther Carvings Museum online photo gallery.

In the ’70s, David Warther’s son, David Warther II started to craft ivory parts from elephant tusks and not long after was introduced to prehistoric mammoth ivory parts. These unique materials were brought from Canada, Alaska and Siberia where it was frozen in the ground for 10,000 to 30,000 years, according to David Warther & Co.

In a statement, Warther Jr. had this to say:

“Ivory as a medium of art in our history as people is a fact of life. It has been with us since prehistoric times when cavemen carved on ancient mammoth tusks. To deny this or to attempt to cover this fact up by removing ivory art from our museums and life is no different than what we see when Islam destroys art pieces because the pieces do not fit the definition of art in the Islamic religion.”

Although history cannot be denied, further practices in the line of ivory can be put to rest, Alles said.

“Cultural practices that sponsor the inhumane treatment of animals, that disenfranchise the earth and lower the moral and ethical standing of human civilizations must end, no matter how ancient or ‘revered’ such practices are considered,” Alles said. “China and Hong Kong have moved in the right direction, dialoguing and legislating to effect the ban of commercial ivory; still, a great deal of work remains to be done in the course of changing hearts and minds and policy.”

Be the first to comment on "Ivory trade: changing minds, hearts and policy"