By Casey Niebuhr | gargoyle@flagler.edu

A day at the beach or a dip in the pool is one of Florida’s great pastimes. However, in 1960s St. Augustine, swimming could have you faced with violent oppression.

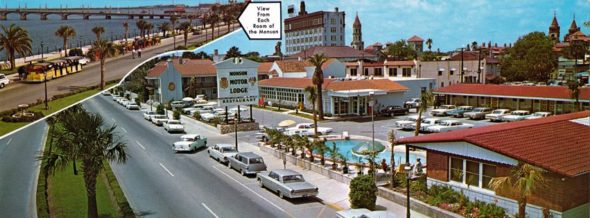

Before the rise of chain hotels dominated American skylines, local inns like the Monson Motor Lodge captivated cities. Located at 32 Avenida Menendez on St. Augustine’s bayfront, the Monson was a hotspot for tourists and locals alike.

Photo from facebook.com

The Monson opened in 1961, replacing the former Monson boarding house that stood since 1884 — not long before the opening of Henry Flagler’s Ponce de Leon Hotel in 1888.

Although the original Monson House had been destroyed twice by fires (in 1895 and in the St. Augustine fire of 1914), it had been rebuilt and expanded over the former half of the 20th century before being demolished in 1960.

The new Monson quickly became a staple of downtown St. Augustine, between the city’s Plaza and Fort Marion. Not only did the Monson have an adjoining restaurant — a place where local police would often convene — but also a waterfront pool: the site of one of St. Augustine’s most infamous civil rights demonstrations.

In the Summer of 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to St Augustine — and so did the media. King had been invited by a local dentist, Dr. Robert Hayling, who was the leader of the civil rights push in the city. King stayed at several safe houses around town, notably with local Janie Price at what is now 156 Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue.

King’s stay in St. Augustine was met with fearful opposition. On June 7th, King was staying at 5480 Atlantic View on Anastasia Island. A leak of his safe house to the press led to the home being shot at in a drive-by. No one had been injured, and despite the clear distaste the city had for his presence, King began to push movement efforts forward.

On June 11th, King was arrested on the steps of the Monson for trespassing. He attempted to eat in the white-only restaurant and, after refusing to leave, was arrested on the behest of James ‘Jimmy’ Brock, the Monson’s manager and president of the Florida Hotel-Motel Association.

King’s arrest at the Monson made national headlines and started a new wave of the civil rights movement in the south — just as King had intended.

On June 18th, a week after King’s arrest at the Monson, over 50 protestors showed up to Downtown’s Monson Motor Lodge. Among them, Rabbi Israel S. Dresner and 15 of his colleagues began a pray-in outside the Monson’s restaurant.

Brock, a deacon and member of the Ancient City Baptist Church for over 55 years, had nearly lost control. With police now on the scene, Brock pushed the demonstrating rabbis toward them to be arrested.

Photo from newscyclecloud.com

Dr. King watched across the street.

As the scene in front of the restaurant consumed everyone’s attention, two activists of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Al Lingo and J. T.Johnson, led a group of supporters to the Monson’s pool.

Shouts and splashing water drew everyone.

Six men and a woman — white and black — swam together in the Monson’s segregated pool. The cameras began rolling.

At this, James Brock had broke. He grabbed 2 gallons of muriatic acid and began pouring the drums into the pool, shouting that he would ‘burn [the protestors] out.’

Photo from rarehistoricalphotos.com

‘I’m cleaning the pool,’ Brock continued, pouring every last drop he could shake out of the drum into the water. His tactic had no effect on the protestors, and a policeman — fully dressed, aside from his shoes — jumped in to drag them out.

Over 100 bystanders watched as the demonstrators were taken into custody. The arrest of Dresner and his fellow colleagues alone has remained the largest mass-arrest of rabbis in United States history.

The following day, on June 19th, King and SCLC had realized their integration tactic had a larger impact than they initially thought: the incident at the Monson had reached national headlines.

The New York Times and The Washington Post had the protest on the frontpage — the same day the Senate was to vote on the Civil Rights Act.

After a 54-day filibuster, the Senate passed the Civil Rights Act 73-27, and on July 2nd then-president Lyndon B. Johnson signed the bill into law.

‘There’s a myth that St. Augustine was the sole reason for the passage of the Civil Rights Act,’ said Michael Butler, a professor of history at Flagler College. ‘It was more of a final push across the goal line.’

But is there any truth to the myth?

‘I think that image of Brock — an iconic photo within St. Augustine’s civil rights history — captured exactly what the Civil Rights Act was meant to overturn,’ Butler said. ‘Congress saw the hatred and fear that was not only occurring within St. Augustine, but the whole United States.’

Upon hearing the news of the bill’s passage in the Senate, Brock not only integrated, but raised a Confederate flag in front of the Monson.

Photo from civilrights.flagler.edu

‘Though Brock integrated the Monson, as was the law, I think by raising the Confederate flag he let the community know where his loyalty had lain,’ Butler said.

Brock would later receive death threats from the Klu Klux Klan for having integrated, and he was caught in a grey-zone. He wanted to be a law-abiding citizen, which would mean going against his personal beliefs. However, in so doing, became an enemy to the very people he shared such beliefs with.

The Monson Motor Lodge gradually lost business and never returned to its heyday of the 1960s. It was demolished in 2003 and replaced by the Hilton Bayfront Hotel, which remains today. James Brock died in St. Augustine in 2007.

In the courtyard of the Hilton, hidden to only those who wish to find it, lie the front steps of the Monson — salvaged from its demolition — with a plaque dedicated to King’s efforts in the Summer of 1964: efforts that had cost SCLC more in medical bills than had litigation fees from any other movement in the United States, including Birmingham and Selma.

Photo from oldcity.com

As Black History Month comes to an end, one may be reminded that one of the cornerstones of the civil rights movement occurred in a spot that no longer exists. The only thing that remains is a set of steps and a plaque — a marker that could never tell the full story — of one of St. Augustine’s many hidden histories.

Be the first to comment on "From Sit-Ins to Swim-Ins"