By Katherine Lewin | gargoyle@flagler.edu

Read below or listen:

St. Augustine, Florida, America’s oldest city, was once a battleground for civil rights. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his supporters were harassed, beaten and jailed when they tried to enter segregated downtown restaurants and swim in segregated sections of St. Augustine’s beaches. A hotel manager once poured acid into a pool where both black and white integrationists were swimming in protest. Dr. King was even in St. Augustine the day that the Senate passed the civil rights bill on June 19, 1964.

This quaint coastal town with its horse carriage rides and sailboats resting quietly in marinas may once again become a battleground for civil rights. Some believe that it has already, especially with the debate over whether or not to tear down Confederate monuments in the downtown Plaza de la Constitución that’s heated up in recent months.

City commissioners voted to “contextualize” the monuments, deciding to leave them in place and adding historical context to them to tell a more complete history.

Bringing St. Augustine back into the civil rights discussion is exactly what Daniel Carter, Jr., 20, hoped to do when he organized the Unity March Against the Repression of a Generation. On Oct. 22, 2017, the National Day of Protest Against Police Brutality, Carter led a group of around 30 people on a march through downtown St. Augustine. This was the first ever protest in the nation’s oldest city organized by the Black Lives Matter movement.

The rally gathered peacefully at the pavilion in the Plaza de la Constitución, which was historically a slave market. The pavilion has been a site of protest for both white supremacists and civil rights advocates going back over 50 years.

“I am black, I do live in America, I do have to deal with what we see every day going on in our country,” Carter said. “And I saw nobody else was making a big deal about it in St. Augustine. If it’s not happening at your back door, then we don’t worry about it, and so I thought that St. Augustine should definitely have a face with Black Lives Matter, and that we should come together and speak out against any white supremacy and let people know it’s not welcome in in our town.”

The movement Carter plans to start in St. Augustine will be similar to what Dr. King hoped to have in the 1960s: peaceful demonstrations, more participation in St. Augustine politics and focus on open-minded dialogue with the St. Augustine Police Department. Carter wants to eventually spark change in the way the United States designs its police forces.

“When I see a cop, I’m terrified. I don’t feel safe at all. Militarization of our police departments is a big issue. They do need to be disarmed and demilitarized now,” Carter said. “We’ve sat down with the St. Augustine Police Department … to have conversations and connect and talk about the issues and not be angry and upset about it.”

- Daniel Carter, Jr., 20, born and raised in St. Augustine, Fla., talks into a megaphone at the Plaza de la Constitution in downtown St. Augustine. The plaza where the march ended was historically a black slave market. Oct. 22, 2017.

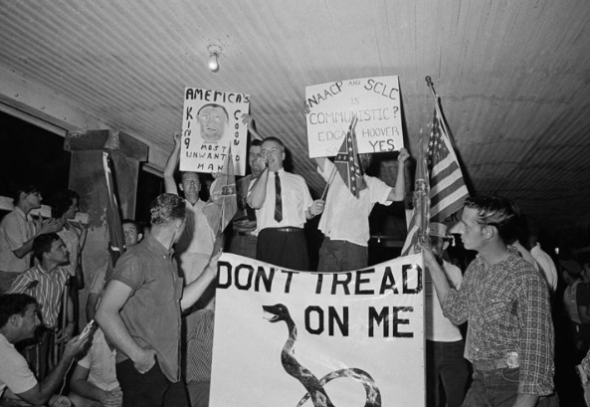

- J.B. Stoner, a white segregationist, addresses a group of whites at the same historic slave market where Daniel Carter would hold his protest 52 years later. June 13, 1964. (AP Photo)

- Protestors gather together on a warm October evening at the old city gates for the march. They marched down St. George Street and attracted a lot of stares and photographs. This was the first rally organized in St. Augustine for the National Day of Protest Against Police Brutality. Oct. 22, 2017.

- African American demonstrators picketing in front of the historic slave market in downtown St. Augustine. St. Augustine Police Chief Virgil Stuart watches. May 30, 1964. (AP Photo)

- Imani Forester, a board member of the Black Student Association (BSA) at Flagler College, holds up one end of a sign and watches the speeches. The organization Black Lives Matter organized this protest in St. Augustine for the first time ever. Oct. 22, 2017.

- Rebecca Guerrier, better known as Becky G., gives a short speech. She is the president of Melanin Vibes, the BSA at Flagler College. The protestors are calling for the disarming and demilitarization of the St. Augustine Police Department.

- J.B. Stoner holds up a confederate flag at the historic slave market before leading white supremacists on a long march through a black neighborhood in Lincolnville. June 13, 1964. (AP Photo)

- Protestors comfort each other in the background after a passionate speech. Tears were shed and emotions were high. Many of the speakers expressed a desire for a police accountability committees and justice for minorities killed by police officers. Oct. 22, 2017.

- Della Long talks about her experience marching with Martin Luther King, Jr. ?King was in St. Augustine, Fla. the day that the Senate passed the civil rights bill on June 19, 1964. He spent several months there helping the city desegregate. Brave men and women of all colors were beaten, harassed, jailed and even burned with acid in a hotel pool by the Oldest City’s own group of segregationists. Oct. 22, 2017.

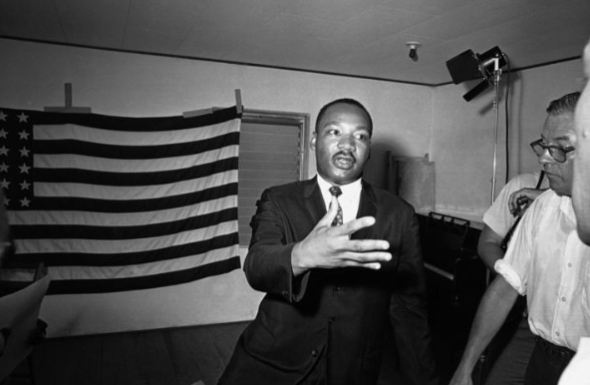

- Martin Luther King, Jr., in St. Augustine, Fla in 1964. (AP Photo)

- Several protestors hold up a ‘Black Lives Matter’ sign while other people speak after the march. On October 22 every year since 1996, people gather all across the United States for a National Day of Protest to Stop Police Brutality, Repression and the Criminalization of a Generation.

- The protest proceeded peacefully with chants of ‘Black Lives Matter!’ and ‘No Justice! No Peace!’ The St. Augustine Police Department donated several officers on bicycles for the protestors’ protection. Oct. 22, 2017.

Be the first to comment on "America’s oldest city again becoming a battleground for civil rights"