By Presleigh Johnson

Public History is everywhere. Whether it’s signs all over St. Augustine, reenactments, or surf culture exhibits, the Oldest City is a treasure trove of history. Being a Flagler College student is one of the best ways to learn about the St. Augustine community.

In 1988, boxes of glass plate negatives were found in the attic of Richard Aloysius Twine’s former house. Just before it was demolished, they’d found a hidden treasure.

It was every public historian’s dream — the chance of rediscovery and history was saved.

The treasure trove of photographs, now uncovered, was acquired by the St. Augustine Historical Society, purchased from a camera store for just $20.00. The 110 photographs showed life in 1920s Lincolnville, the historically Black neighborhood just off King Street in downtown St. Augustine.

Lincolnville was founded in 1866, just one year after the Civil War ended. In Jim Crow-era Florida, Lincolnville became the commercial, social, and spiritual center for Black St. Augustinians who were forced to live within the confines of segregation. By the 1920s, Lincolnville was a thriving neighborhood with shops, entertainment spaces, restaurants, and residences.

Ranging from interiors of churches to portraits of teachers, Twine captured life in Lincolnville from 1922-1927. Let’s take a look at the world Twine left behind for us.

Twine would photograph locals like Mildred Parsons Mason Larkins (pictured below), who remembered being photographed by him several times. One of Larkins’s sons, Otis Mason, became the first St. Johns County Superintendent of Schools of African-American descent. Twine documented everyday people in the community while also showing the era’s finest fashion.

(Photo Courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

Ocie Martin was also photographed by Twine. She was known for her singing voice and her pet parrot, which I personally would like to know more about (perhaps a topic for another column).

(Photo Courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

From children in school play costumes to family portraits, Twine photographed a variety of different community members. His photography extended beyond people, including businesses, celebrations, buildings, and even funerals.

Palace Market was one of the businesses he photographed and I chose this one because when I look at it, I feel like I’m right there, about to enter the market. Twine composed the photograph to seem so personal.

(Photo Courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

Snyder’s Store (55 Bridge Street), another business Twine photographed, was run by Sol and Sarah Snyder who moved to St. Augustine from Russia in 1906. Some of the store’s items were supplied by their farm, so customers could expect farm-fresh meats and friendly service. The store serviced members from both Black and white communities.

(Photo Courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

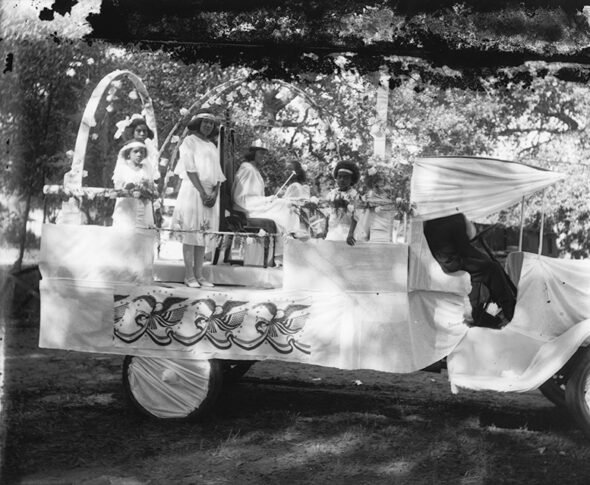

Thinking of community life, Twine snapped photographs of floats from an Emancipation Day celebration, including the Queen and her court driving by.

(Photo Courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

St. Benedict the Moor Catholic Church was photographed by Twine. At the time, it was a popular location for mass for Black and white communities, being smaller and quainter than the Cathedral Basilica in the middle of downtown. Twine photographed the St. Benedict Catholic School (pictured below), too, which closed in 1965 following the parochial schools’ integration.

(Photo Courtesy of the St. Augustine Historical Society)

These photographs show us a bit of Twine’s work, but who was Richard Twine? He was born in 1896 in St. Augustine and might have picked up his photography skills in New York City. He operated a studio on one of Lincolnville’s main commercial street (62 Washington Street), until he moved to Miami in 1927 to start a business with his brother. He died in Miami in 1976, but the snapshots of life he captured in Lincolnville live on.

After the Historical Society acquired the photographs, they worked with Flagler College students to preserve them, spending more than 100 hours in the darkroom. Twine’s photographs display a world that would change just after he left St. Augustine when the financial effects of the Great Depression arrived in his hometown.

(Photo Courtesy of Magen Altice)

Dr. Jeanette Vigliotti, Assistant Professor of Classic and Liberal Education CORE at Flagler College and Education Outreach/Editor-in-Chief at the St. Augustine Historical Society, has curated an exhibit on Twine. She says, “Twine’s photographs in particular are a glimpse into the thriving businesses and vibrant community of Lincolnville in the early parts of the twentieth century.”

Dr. Viglotti frequently teaches Lincolnville’s history in her classes because “the contributions of Black St. Augustinians in Lincolnville are just as vital to St. Augustine’s development as some of the more familiar historical figures such as Henry Flagler or Pedro Menendez.”

Lincolnville’s history has been an under-explored part of the St. Augustine story, but I hope that we are at the beginning of a Lincolnville renaissance, where its story of community and resilience is shared with the public.

Twine’s photographs are an entry point into learning about Black history in St. Augustine and the stories of its community members. Without his eye for community life and his camera to capture it, so much of the city’s history would be lost.

Click here to view more of Twine’s photographs.

Learn more about Lincolnville by visiting the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center.

Check out more of St. Augustine’s Black history.

Search the St. Augustine Historical Society’s database for more information on Twine.

Be the first to comment on "Richard Twine’s World: Life in 1920s Lincolnville"