By Danielle Filjon

Like many coastal areas, St. Augustine is familiar with the sight of eroded shorelines after a major storm. Along with destroying homes, erosion also damages vulnerable ecosystems, leaving every aspect of the coast affected by hurricanes and tropical storms.

But a tiny hero — the humble oyster — may just have the power to help prevent some of this devastation.

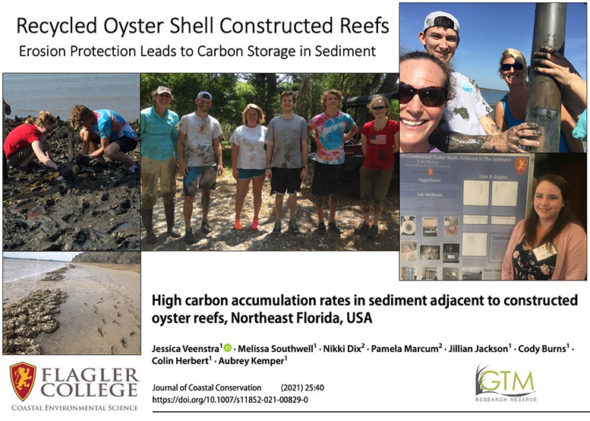

Researchers and students at Flagler College and the Guana Tolomato Matanzas National Estuarine Research Reserve (GTM) teamed up to discover the power of the oyster in our local shorelines.

Along with the longstanding patterns of erosion, the oysters themselves are in trouble, a large majority of the global oyster cover has been lost over the past century. These oysters hold keys to adding necessary carbon lost from climate change back into our ecosystems and atmospheres as well.

“Our research was looking at the sediments surrounding a constructed oyster reef,” said Dr. Melissa Southwell, a professor and researcher at Flagler College. “Oyster reefs have been in decline over the past decades, and they’re really important to the ecosystem, so there’s a big push to restore and construct oyster reefs.”

The 114-mile research and nature preserve is well-known in St. Johns county for its extensive hiking trails and critical research about the land’s ecosystem.

This team constructed and studied the benefits of an artificial oyster reef on shoreline erosion and sediment in the area. The reef was made out of oyster shells that GTM volunteers collected from local restaurants that were destined for landfills.

“GTM had the initiative to construct artificial oyster reefs with their volunteers to combat the shoreline erosion. We saw this as an opportunity to monitor the changes that happened in the sedimentary environment, before and after they installed the reef,” Southwell said.

The oyster reef site at GTM was constructed to control erosion along the shoreline and monitor changes in the sediment around it; the oyster reefs encouraged a deposit of thick mud rich in carbon. This has positive implications when facing the global problem of climate change.

“When you deposit that kind of organic, rich sediment like that, it protects it from oxygen, so it’s less likely to break down and return as CO2,” Southwell said. “And so, this is what we call sequestering carbon, which means stocking carbon away so it cannot be recycled as carbon dioxide that is then released into the atmosphere.”

Dr. Jessica Veenstra, the Department Chair of Natural Sciences at Flagler College was also a part of the research team who led students and worked with the researchers.

“If [the oyster reefs] are protecting the shorelines, we can see that they are accumulating carbon there,” Veenstra said. “This becomes a small opportunity to mitigate climate change.”

The reef at GTM was successful initially, but fell apart over time due to large weather events. Many researchers who are trying to implement the same type of reef structure are struggling with the design aspect to keep the reef together during large storms and tides.

“It was unfortunate that our reef fell apart, but it’s great in a scientific sense because we and other researchers can learn from it and improve designs,” Veenstra said. “I have heard of suggestions to use concrete in the reefs to make them stronger, so that could be a new idea.”

Even if this specific trial didn’t go as planned, Veenstra says that above all, this experience for her students was the top priority.

“Students out there sampling sediments were up to their knees and hips and mud, you know? That is, that’s really fun. And I really enjoy that,” Veenstra said. “It’s their opportunity to learn how to do field work and lab work and to add that to the resume. That’s what motivates me about this work.”

The team gathered significant data over the course of their study, the Flagler professors and students involved with the research published a paper about the collection of carbon in the sediment formed by the oyster reefs, as well as possible implications for shoreline protection.

“This living shoreline was for erosion protection and a habitat for organisms while absorbing of the energy associated with high-impact weather events. I would love to see the local government make choices that include these types of oyster projects on our shorelines,” Veenstra said.

The humble oyster shell, once someone’s dinner appetizer, has the potential to be a strong wall for shoreline erosion, and add essential carbon to the sediment surrounding it. Research of this kind is ongoing, hopeful, and crucial for finding new resourceful solutions to the world’s ever-evolving climate and environmental issues.

The paper published by the Flagler professors is in the Journal for Coastal Conservation.Read here: High carbon accumulation rates in sediment adjacent to constructed oyster reefs, Northeast Florida, USA | SpringerLink

Be the first to comment on "Using the humble oyster to save our shores"