By Adam Hunt | gargoyle@flagler.edu

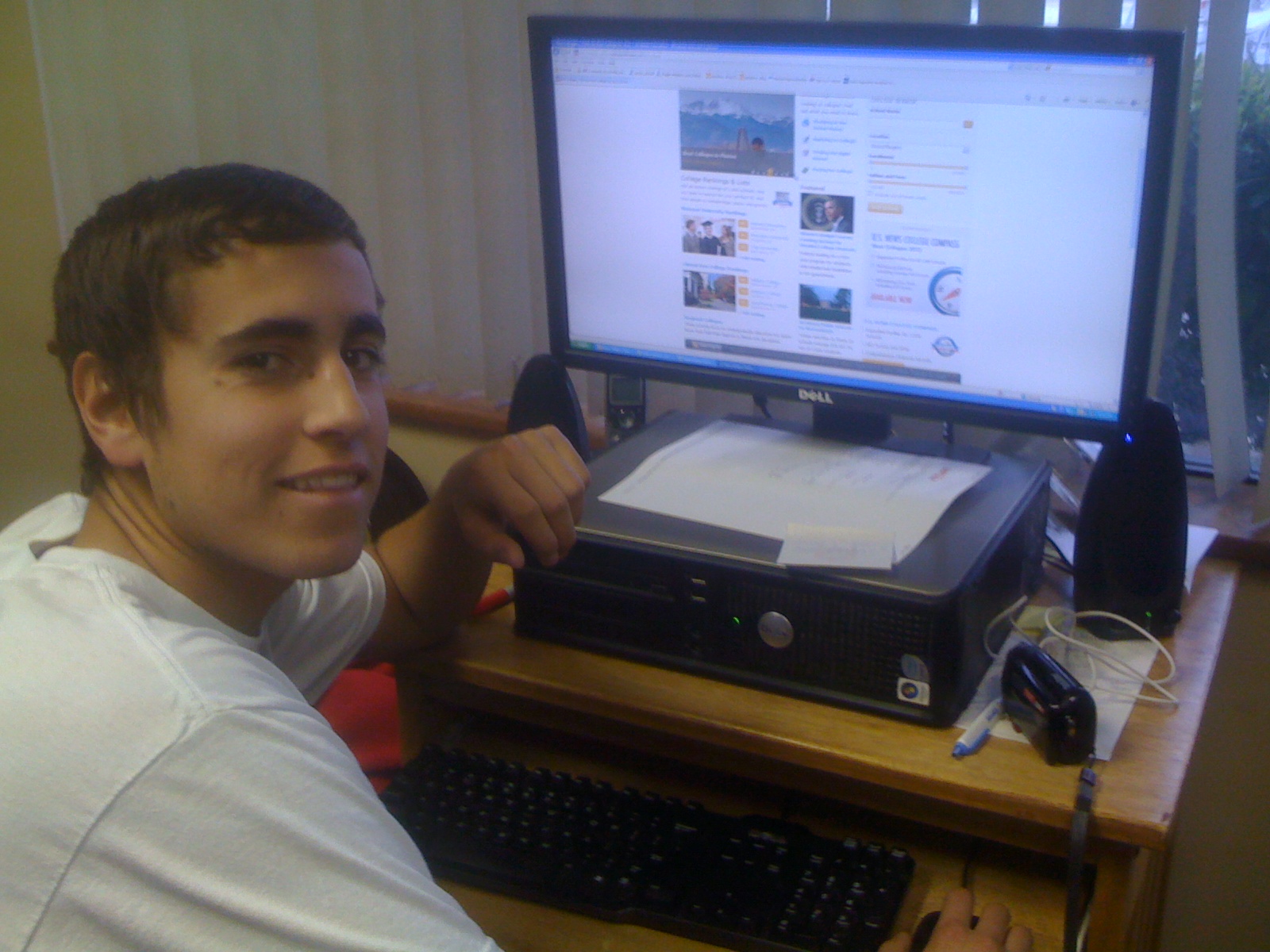

It was the first thing David Espinosa looked at when choosing a college.

The 19-year-old Flagler College student never doubted the validity of the U.S. News & World Report’s Best Colleges rankings.

Being from Ecuador and unable to afford a trip to visit American colleges and universities, rankings lists were an essential tool in his search for a place to study.

“The rankings were very important to me,” he said. “When I received my SAT results I used them to find schools that would accept me. I naturally trusted what I read.”

For Espinosa and millions of other students considering higher education, the yearly U.S. News list, published in print and online, represents the most influential of all college rankings.

But its reputation was called into question recently as Claremont McKenna, a renowned liberal arts college in California, admitted to falsifying the average SAT scores it had submitted to U.S. News since 2005.

It is the latest in a series of scandals involving colleges altering data such as acceptance figures, test scores, graduation rates and student-faculty ratios.

Baylor and Villanova Universities, as well as the United States Naval Academy are just some of the notable institutions to have also been caught fudging their numbers.

Because of the sheer volume of data used to calculate its rankings, U.S. News operates largely on an honor system.

As in the Claremont McKenna case, faulty figures can go unnoticed for years and may only be discovered by the institution itself.

“We have a research office with software that automatically generates accurate data,” said Derek Hall, vice president for university and external affairs at Jacksonville University. “But there are no strict guidelines. It would be virtually impossible to detect an individual person changing a few numbers.”

Despite the blows to its credibility and the various alternative rankings available, the U.S. News list still remains the first choice for most students and parents.

A study conducted by Harvard Business School in 2011 revealed that a climb of just one spot in the rankings leads to a 1 percent increase in the number of applications a college receives.

“They are seen by many students and officials as a measure of an institution’s inherent worth or quality,” said Eric Hoover, a senior reporter at The Chronicle of Higher Education. “An individual student may hold on to one piece of data for a long period of time and, in the end, choose the school with the better looking scores simply because it is easier to justify.”

But local college officials aren’t so sure.

“In my experience, a student’s first impression when they land on campus is almost always the most decisive factor,” said Thomas Serwatka, vice president at the University of North Florida. “If the student doesn’t feel like the college cares about them, then it doesn’t matter what the rankings say.”

Be the first to comment on "Local students still hooked on college rankings"